Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists - Bulliet

C. J. Bulliet, The Chicagoan, Vol 12, No. 4, November 1931

Click to view full image

The Front Steps by Gustaf Dalstrom

Click to view full image

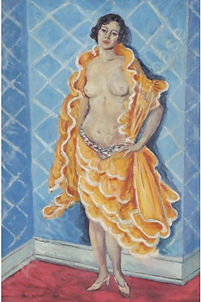

The Dance by Fred Biesel

Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists

All the glower of the war clouds could not blot out completely the vision of the dazzling dawn that was the Armory Show in the memory of Chicago artists with creative impulses, and while most of them may have been a bit wary about flaunting their creations in the faces of neighbors who already regarded them as anarchists and bolshevists, their instincts were clamoring for expression.

Origins and Founding Principles

The bold stand of the Arts Club, starting about Armistice Day, against the powers of darkness and suppression was tonic. Exhibition of new art was not destined to begin and end with the Armory Show.

There was a further bracing up in courage in contemplating a few rash rebels who had dared to carry on, in a creative way, even while the war government's "Division of Pictorial Publicity" was functioning.

The most picturesque of these was Stanislas Szukalski — the most picturesque figure, indeed, in the entire history of art in Chicago. He was only 19 when the war broke out and had been here only a year from his native Poland. Within the year, he was already the sensation of Chicago's "bohemia," with his long hair, his "tam" and his extravagant clothing.

When war was declared, he declared himself against war. But that didn't prevent his carrying a thick cane, which he swung savagely as he walked, viciously cutting off the heads of imaginary foes after the manner of a cavalryman with his saber.

Szukalski had his share of trouble with the military authorities, but his picturesque personality along with his amazing, precocious genius as painter and sculptor, had won him many powerful friends, so he always managed to escape with his neck still a practical working unit.

Szukalski, Rudolph Weisenborn, C. Raymond Jonson, Helen West Heller and some others were painting radical things and inspiring other radicals to paint.

But where exhibit?

The Art Institute offered two annual possibilities—the All-American Show in the autumn and the exhibition by artists of Chicago and vicinity in the late winter or early spring. To the juries of these annuals, the rebels sent their work, either boldly or timidly, but in either event with the certainty it would be rejected. For the Art Institute, in those ghastly days of the war and the "red menace," was repenting the Armory Show in Chicago 1913, regretting its mistaken sense of hospitality in housing those anarchistic pictures.

Lorado Taft, then czar of Chicago art in the division of sculpture (the late Oliver Dennett Grover was painting czar) was the institute's Scammon lecturer in 1917, and in a series of six discourses on "Modern Tendencies in Sculpture," he proceeded to put in their place a number of the workers in marble who had exhibited in the Armory Show, along with others of their stripe.

The witty Taft showed photographs of sculpture by Matisse, Brancusi, Archipenko and Gaudier-Brzeska, among others.

"This one," he said, "is the work of the notorious painter, Matisse. You see he is quite as good a sculptor as he is a painter." "This other one is Brancusi's Kiss. Brancusi the author of the far-famed Mlle. Pogany, which, we are assured, is 'not a servile reproduction of features,' but an interpretation of the soul. Perhaps its companion entitled A Head is Miss Pogany's sister's soul, although it has been called The Mislaid Egg."

And, in a footnote to the lecture at this point, when printed, Mr. Taft asserted: "The men who produced these last-mentioned curiosities are presumably aliens in France, but their so-called art was inculcated and brought forth in Paris through the hospitality of a public which is ever seeking 'some new thing.' The information obtainable about their shadowy personalities is so slight and so contradictory that some have been tempted to believe them fictitious—a syndicate, or possibly a 'Mr. Hyde' manifestation of some perfectly reputable artist."

Yet Brancusi, Archipenko, Matisse, Bourdelle, Maillol had exhibited in the Armory Show at the Art Institute of Chicago four years before the Taft lectures, and they were not "shadowy personalities" to Arthur Jerome Eddy, Chicago businessman.

But the Scammon lecturer was the "authority" deemed competent by the Art Institute in 1917 to instruct its members and its students as to "Modern Tendencies in Sculpture." The institute, as doubtless was policy, walked in the ways of political rectitude and anti-bolshevism like a very dollar-a-year man.

As thought the institute, so thought its juries — and it had a most marvelous jury system. The jurors, twenty-one in number, were selected each year by vote of artists who had been in exhibitions juried by this body within the past three years. Consequently, the kind of artist who had exhibited would vote for the kind of juror who had permitted him to exhibit and who would doubtless permit him to exhibit again.

Rebellion Against Traditional Juried Exhibitions

In 1921, the Art Institute's jury mill ground out the same old grist—not a "liberal" picture was accepted for display.

When the rejection slips were made out and the character of the forthcoming show was made apparent, three rebels put their heads together—Rudolph Weisenborn, Carl Hoeckner and C. Raymond Jonson.

Why not a "Salon des Refusés"?

Such an exhibition of the rejected way back in 1863, with Manet as chief rebel, had broken ultimately the power of the art czars of Paris. Why not try its effect on the Chicago czars?

But how know who were the Art Institute's "rejected"? The slips were (and still are) sent out confidentially. Two or three or a dozen artists can get together, compare notes, and find out who have been refused, but to make a "Salon des Refusés" effective, all the rejected must be known.

Also, supposing they could get a list where could a show be staged properly — a staging that must match as nearly as possible the show at the institute, whose rival it was to be? Napoleon III, in the Paris of 1863, had ordered the "Salon des Refusés" under the same roof as the official show—but there were no Napoleons of tendencies like that in Chicago. Still, as it turned out, there was no need of anyone of Napoleonic proportions.

An official of the department store of Rothschild & Company, at State and Van Buren streets (now the Davis store) came to the rescue. He was a friend of Weisenborn’s and a lover of art, if not for itself, then for advertising purposes, and had invited Weisenborn before to assemble some sort of show or other for him.

Not only did this merchant like the “Salon des Refusés” idea, but he grew enthusiastic about it and offered to spend as much as $50,000 if necessary to assemble and exploit the exhibition.

Weisenborn and his friends then approached Director Robert B. Harshe of the institute. Mr. Harshe, whose ideas are liberal, as we have noted before, liked the suggestion but couldn’t see his way clear to furnishing a list of the rejected. It was a day of diplomacy, however, in world affairs, when ministers of state were constantly exchanging ideas and devising ways and means.

Impact and Legacy in Chicago’s Art Scene

Finally, after three or four sessions, Mr. Harshe agreed that the institute would send out a letter on institute stationery, written and signed by Weisenborn and his committee inviting participation in a “Salon des Refusés” at the Rothschild store. This would be no violation of confidence on the part of the institute—the Weisenborn committee would never know to whom the letters were sent except as the receivers of the letters replied to the invitation—and that was wholly up to the recipients.

Responses began pouring in immediately. A huge section of the eighth floor of the Rothschild store was cleared and converted into galleries, and the Chicago “Salon des Refusés” became a fact. The French was a bit difficult, even for the artists, and the exhibition became known popularly as the “runaway show.” It was the first “independent” art show in Chicago since the Werntz and Kahler shows in the war years.

Rothschild & Company kept their word about exploitation. But soon the publicity was clear out of their hands. The newspapers took it up as a news sensation, and crowds began passing eagerly back and forth between the institute and Rothschild’s and milling about excitedly in both sets of galleries, comparing, praising and condemning. Not since the Armory Show had Chicago had so good a time artistically.

The “critics” tore their hair, “old hats” groaned, scribblers of anonymous letters threatened. It was well the Art Institute had a jury to screen Chicago from atrocities like these!

Meanwhile, Rothschild & Company were doing a land office business in suspenders, shoelaces, corsets, garters, or whatever knick-knack the visitors needed at the moment and saw on display in the aisles leading to the “Salon des Refusés”—getting back rapidly that $50,000. It was a graceful gesture and a sound business venture as well.

Marshall Field & Company took notice, and Harrison Becker, in charge of the art department, consulted his friend, Charles Biesel, painter of marines, exhibiting in the “Salon.” Biesel put Becker in touch with the triumvirate, Weisenborn, Hoeckner and Jonson, and Marshall Field & Company opened negotiations for any future show of this sort which the “independents” might want to stage.

Why not make it an annual affair?

The triumvirate and Biesel called in some other artists and literary friends as advisers—among them were Ben Hecht, Sherwood Anderson and Sam Putnam.

Instead of depending on the “rejected,” it was thought best to start a society patterned after the New York Independents, who had been functioning for some little time—patterned, in turn, after the Paris Independents. John Sloan, moving spirit of the New York Independents, and a friend of Biesel’s, had suggested some such Chicago organization, and Biesel laid the suggestion now before the assembly.

Those present fell in with the idea. Weisenborn was elected president, Biesel secretary, and Biesel’s artist daughter-in-law, Frances Strain, treasurer.

Difficulty was encountered choosing a name. Some of the artists didn’t care for a motion to call themselves Chicago Independents—it would look too much like a colony of the New York organization.

Helen West Heller suggested “No-Jury,” as expressive of the determination to have done with the Art Institute methods. The idea was accepted as a happy one, and the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists was ready to order its stationery. (Charles Biesel, to make the action unanimous, voted against his judgment for the name. "I believe," he tells me in retrospect, "it killed every prospect of our ever-making sales—the public believing a picture passed by a jury O. K. of course.")

A committee was appointed to help the officers carry out their plans, mostly from exhibitors in the "runaway show" — Karl Mattern, Minnie Harms Neebe, Datus E. Myers, Carl Hoeckner, Louis Alexander Neebe, Mae Larsen, Sam Ostrowsky, Marie Macpherson, Helen West Heller and Fred Biesel, son of Secretary Charles and husband of Treasurer Frances Strain.

Among other exhibitors, besides members of this new committee, in the "runaway show," who have persisted prominently in the art life of Chicago ever since, were Jean Crawford Adams, heading the list arranged alphabetically, and now one of the few Chicago artists sponsored by the Chester Johnson galleries; Claude Buck, accepted later by the Art institute to the extent of a one-man show; Charles H. Cooke, who divides his allegiance now between No-Jury and Palette & Chisel, of the left wing of this latter sleepy club and of the right wing of No-Jury; Robert Lee Eskridge, Chicago bohemia's envoy to Gauguin's South Sea islands; Charles E. Mullin and Paul Plaschke, both of whom participated in the first of all Chicago's radical exhibitions at the Werntz academy in the summer of 1915; Carl Newland Werntz himself, Agnes Squire Potter, Gregory Prusheck, Josephine L. Reichmann, William S. Schwartz, Eduard Buk Ulreich and the Spaniard Ramon Shiva, who, as friend of Weisenborn and Sam Putnam, became in later years a power in "art politics" in Chicago—one of another triumvirate, that ruled the Rush Street colony.

The first exhibition of the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists opened in the galleries of Marshall Field & Company Oct. 2, 1922. Three hundred and sixty-five canvases were hung as against the two hundred and ninety-one in the "runaway show." Among new “no-table” names of Chicagoans in the first No-Jury catalogue are Anthony Angarola, Emil Armin, Gustaf Dalstrom, Frances Foy, Vinod Hannell and Gordon St. Clair, all of whom were already rising out of the multitude.

It was a day of manifestos, and so No-Jury had to have one. Here are some paragraphs from the “Foreword”:

“The efforts of juries to maintain a high standard have usually done injustice to young, unknown talent. Such ‘high standards’ are generally standards of the past; they are chains by which the free development of art is hampered. “Considering the fact that the very men who were the makers of our art history have, almost without exception, been rejected by the exhibition juries, we can only conclude that this system is a failure and that any new system which allows the free development of creative ability be encouraged. “The public as well as art experts and critics should keep the following quotation from Manet’s debates in mind: ‘Men capable of appreciating painting at its first appearance are as rare as those capable of creating it.’”

This last pronouncement threw one of Chicago’s veteran lady newspaper critics into such a panic that she announced to the sponsors of the show that, since they were singling out no pictures for prizes and were hanging the works alphabetically, she wouldn’t undertake to praise or blame any individual pictures, but would write a vague “general story” of the show. This declaration pleased the sponsors quite well, since the lady was a determined worshipper of the institute and believed the institute juries could do no wrong and make no mistakes.

This reverence of the lady critic for juries was destined to be rudely jolted. For the “radicals,” drunk with the success of their “runaway show” and with the launching of No-Jury, looked for other worlds to conquer, and they laid a plot against the institute jury itself.