Palette Club (Bohemian Art Club) of Chicago

By Joel S. Dryer

Click to view full image

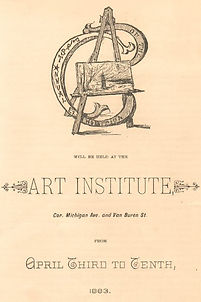

Bohemian Art Club first exhibition 1883 at the Art Institute of Chicago

Click to view full image

Palette Club & Cosmopolitan Art Club joint exhibition, Chicago, 1895

Bohemian Art Club of Chicago

Palette Club of Chicago

Origins of the Club

The history of Chicago’s art world in the late nineteenth century cannot be told without acknowledging the profound contributions of the women who formed, nurtured, and sustained the Bohemian Club—later renamed the Palette Club. Their story is one of ambition, resilience, artistic camaraderie, and the pursuit of institutional legitimacy in a male‑dominated cultural landscape. While the extant texts chronicling their journey are scattered, uneven, or fragmented, the narrative that emerges from them is a compelling testament to how a determined group of women helped build and shape Chicago’s artistic identity. The club’s archives and records were unfortunately destroyed in the Athenaeum Building fire of 1892. What we have for history comes from multiple newspaper and magazine accounts and exhibition catalogs. The following essay synthesizes these historical materials into a cohesive account, while preserving, verbatim, every direct quotation from contemporaneous sources.

Influence of Marie Koupal Lusk

The Bohemian Club began in 1880 in the studio of Marie Koupal (later Lusk), a Bohemian‑born artist whose heritage inspired the club’s whimsical name.[1] As recorded, the group was founded in the studio of Marie Koupal Lusk in the Fall of 1880, who was Bohemian, and after whose lineage the play on words was taken.[2] The club’s earliest purpose was not formal exhibition but fellowship—an intimate gathering of twelve women artists who met for “comradeship in sketching and criticism.”[3] However, within a few years, membership required passing an examination and submittal of works to a committee to decide upon the artist’s merit.[4] What began as a private circle of practitioners soon expanded, establishing regular Saturday meetings by 1882 in the studio of Ida Burgess, another founding member.

Critical Praise

This shift from informal artistic fellowship toward more structured ambition manifested in their first public exhibition. Their inaugural annual exhibition opened in the spring of 1883 at the Art Institute of Chicago, marking their transition from a private sketching group to a public artistic presence.[5] Contemporary reviews provide rich insight into the reception of their early efforts.

One critic wrote:

The first annual exhibition of the Bohemian Club was opened by a reception at the Art Institute last evening. The Bohemian Club is composed entirely of ladies, most of them professedly amateurs. The exhibition has been anticipated by many people interested in art with a sort of deprecatory hope for success. The pictures were hung yesterday, and last evening the summoned guests filled the inviting rooms and large gallery of the Art Institute to overflow…. The gentlemen of the Art League turned out to gallant force, and worked under the directions and suggestions of the exhibitors [to hang the exhibit for the ladies]. The result is a success. The work shown is of a much higher order of excellence even than was to have been expected…. the general average of the work was good. Gay and Erwin and Macdonald, of the Art League stood together talking of the decided success of the Bohemian exhibition. "It is better than ours," said one of them, and presently a second whispered, "It might be a good plan for the League and the ladies to have an exhibition together."[6]

This mixture of gentle praise and gendered skepticism characterized much of the contemporary reception of the Bohemian Club’s early exhibitions. Still, the women persisted, producing increasingly mature work in oil, watercolor, drawing, and sculpture. By their second exhibition, the tone of criticism had shifted notably. A reviewer observed: “The exhibition of the Bohemian Art Club at the Art Institute Gallery continues to attract many visitors. Its success is very gratifying to the members of the club who have worked so patiently and persistently, and, withal, so quietly, that they have surprised even the friends who have watched their progress.” The reviewer further noted that the strength of the club lay “mostly in the works in oil, the aquarelles being in the minority both in numbers and importance.”[7] Here the emphasis, notably, was on artistic merit, not gender.

Club Growth

By the mid‑1880s, the club had grown substantially in both membership and ambition. During the summer, sixteen members “went together to a farmhouse in Wisconsin,” transforming rural retreats into productive summer sketching excursions.[8] Such efforts demonstrated their willingness to align themselves with prevailing artistic practices—plein‑air painting, communal study, and immersion in natural scenery. The president at that time was Mrs. Elizabeth Livingston Steele Adams.[9]

Fifth Annual Exhibition

By the fifth annual exhibition, the club had moved its venue to Stevens’ Gallery. The review published that year highlighted the increased scale and seriousness of their work: “This club has a membership of twenty-eight women, all of them. Less than one-half earn their living by the brush, but all of them have the definite ambition which belongs to the practical artist.” Their exhibitions, the critic noted, displayed “a portion of this work” each spring, with the fifth show boasting “A hundred and seventy-five pictures.”[10]

This was a remarkable achievement. At a time when professional opportunities for women artists were limited, these women not only produced work at considerable scale but also succeeded in cultivating a supportive and disciplined artistic community. Their ambitions were validated in 1888 when they officially changed their name to the Palette Club, a shift that reflected, as the record states, “that names increased dignity and importance.” Chicago had recognized them not just as a women’s novelty group but as a serious artistic institution.

Growing Reputation in Chicago

The Palette Club's reputation grew steadily. At one exhibition, a headline declared: “Creditable Compositions in Oil and Water Colors Which Average Better than Those Recently Shown by the Chicago Society Artists.” This comparison—unfavorable to the all‑male Chicago Society of Artists—was unprecedented. The review noted that “the work is of a better average, in both oils and water colors than that of the Chicago Society artists which recently preceded it,” a clear affirmation that the Palette Club had achieved parity, if not superiority, to its male counterparts.

Their organizational practices also grew more sophisticated. By 1891, members were meeting on Saturdays to “submit sketches illustrating some story which was read the previous Saturday,” demonstrating their commitment to narrative structure and conceptual cohesion.[11]

Despite this loss of club records in the 1892 fire,[12] the club recovered quickly, securing permanent sales space in Chickering Hall and soon after exhibiting prominently at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, where “75 feet of wall space was allotted their exhibition in the Illinois Building.”[13]

The 1890s saw continued growth and diversification of the club’s membership. By 1894, the Palette Club boasted “more than seventy artists of which about one-third had studied abroad.” Many had trained in Paris, Munich, or other European centers, reflecting the increasingly international profile of Chicago’s art community.

Joint Exhibition with the Cosmopolitan Art Club of Chicago

By 1895, the Palette Club had become the city’s oldest active art organization. That year, they entered into a joint exhibition arrangement with the Cosmopolitan Club, an all‑male offshoot of the Chicago Society of Artists. Although the clubs “maintained separate juries and galleries in the Art Institute,” some women exhibited in both sections.[14] This collaboration—with its combination of separation and overlap—symbolized the evolving yet still unequal landscape of professional art in Chicago.

Their final joint exhibition in 1896 was, by all contemporary accounts, their finest. One article described the opening reception: “Artists and art lovers met together at the Art Institute last night to look at new pictures, drawings, and sculpture.” The south galleries “were so thronged many forgot to look at the art exhibit, but watched the crowd of people instead.” Most notably, the review praised the Palette Club artists specifically: “Those who have attended former receptions said the Palette club’s showing was the best in its history.”

Merger With the Cosmopolitan Art Club

By 1897, the Palette Club—still vibrant but increasingly absorbed into larger institutions—merged into the Cosmopolitan Art Club. Later that year, the club formally disbanded.[15] A newly consolidated Exhibition of Works by Chicago Artists began at the Art Institute, incorporating the legacies of the earlier art clubs into a single citywide showcase.

Exhibition History

Up to and including the 1895 joint exhibition, the club had annual exhibits as follows:

April 3, 1883 (1st) | March 14, 1884 (2nd) | April 29, 1885 (3rd) | April 2, 1886 (4th) |

April 14, 1887 (5th) | April 2, 1889 (6th) | April 2, 1890 (7th) | April 24, 1891 (8th) |

April 25, 1892 (9th) | Dec. 1, 1892 (10th) | Feb. 1, 1894 (12th) | Jan. 24, 1895 (13th) |

December 12, 1895 (14th).

Hamlin Garland's Epilogue

As a kind of epilogue to their independent existence, Chicago author Hamlin Garland offered a thoughtful and provocative essay on the nature of artistic production in Chicago. His remarks, preserved fully and quoted verbatim throughout, critiqued the idea that Chicago lacked the proper “art atmosphere.” “It is generally believed that conditions for the production of art in Chicago are especially hard,” he began, “but from this belief I must dissent.” Garland argued that artistic genius arises not from atmosphere but from individual creative force: “Monet makes Giverny. Giverny does not make Monet.” He cautioned against imitation, arguing that artists must pursue “our individual and wholly original contribution to the art of the world.”

Garland’s essay also addressed the psychological and economic challenges faced by Chicago artists—ranging from “an almost insurmountable prejudice on the part of picture buyers” to the insistence that artistic legitimacy must be earned in Paris before being recognized in America. His critique of this bias remains resonant: “This intellectual timidity — to call it by its least offensive name — which buys a picture on the strength of the salon label, and not upon individual judgment…”

In his closing remarks, Garland spoke directly to the artist’s obligation to sincerity and originality: “Hold the Western artist to a rigidly high standard, but do not make the fatal mistake of substituting tradition for vitality, imitation for originality, dead canvas for nature.” This message, written in 1895, stands as a fitting philosophical companion to the Palette Club’s history. For sixteen years, the women who formed and sustained the club embodied many of the principles Garland articulated—originality, sincerity, self‑reliance, and courage.[16]

Their exhibitions, their camaraderie, their educational and professional endeavors, and their eventual integration into the broader Chicago art establishment collectively illustrate a critical chapter in American art history. They were pioneers not only in their creative pursuits but also in forging institutional pathways for women artists who would follow.

[1] For a review of their history see, Maude Elliot, editor, Art and Handicraft in the Woman’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Report of the Illinois Woman’s Exposition Board. Section of the Fine Arts, (Chicago: Illinois Woman’s Exposition Board, 1894), pp.45-47. It was incorporated as the Palette Club, after a name change, in 1892. Announcement of incorporation is made in “New Incorporations,” Chicago Tribune, 11/16/1892, p.10. For a review of Lusk’s early career see “Art In Chicago: A Case of Genuine Genius Which Should Be Encouraged,” Chicago Tribune, 8/14/1891, p.6.

[2] “A Lady Who Is Prominent Among Chicago Artists,” unknown source, Art Institute of Chicago Scrapbooks, 1891, vol. 5, p.42. Confirmed in “Art and Artists,” Graphic, 2/20/1892, p.136.

[3] “Art In Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, 4/10/1881, p.6.

[4] “The Palette Club: Old Friends Under a New Name Give a pleasing Art Reception,” Daily Inter Ocean, 4/3/1889, p.6.

[5] “Art And Artists,” Chicago Tribune, 4/15/1883, p.10.

[6] “The Bohemian Club,” unknown newspaper, 4/4/1883, scrapbook of Alice Kellogg Tyler, courtesy of Joanne Bowie.

[7] “Chicago Art,” Chicago Tribune, 3/23/1884, p.11.

[8] “Notes from the Galleries and Studios,” Chicago Tribune, 7/23/1882, p.7. S. R. Koehler, compilation, The United States Art Directory and Year-Book (New York: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. 1882). p.27. They later continued to practice of taking summer jaunts into the nearby countryside for a few weeks. For example, in 1887 they were at St. Joseph, Michigan and in 1886 at Ottawa, Illinois.

[9]“Art and Artists: Notes,” Daily Inter Ocean, 12/23/1882, p.9.

[10] “The Bohemian Art Club,” Chicago Tribune, 4/27/1887, p.9.

[11] “Palette Club Exhibit,” Morning News, 4/25/1891, AIC Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, p.39.

[12] Annette Blaugrund, “Alice D. Kellogg: Letters from Paris, 1887-1889,” Archives of American Art Journal. Vol. 28, No. 3, 1988, pp.19.

[13] “Among The Artists,” Sunday Inter Ocean, Vol. XX1, No. 224, 11/6/1892, Part 3, p.21.

[14] “Artists To Exhibit,” The Chicago Tribune, 1/21/1895, p.3.

[15] Charles Francis Browne, “Chicago 1897,” Arts For America, Vol. 7, No. 5, January 1898, p.301.

[16] Hamlin Garland, “Art Conditions in Chicago,” United Annual Exhibition of the Palette Club and the Cosmopolitan Art Club, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 01/24/1895), forward.