Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors

By Joel S. Dryer

Click to view full image

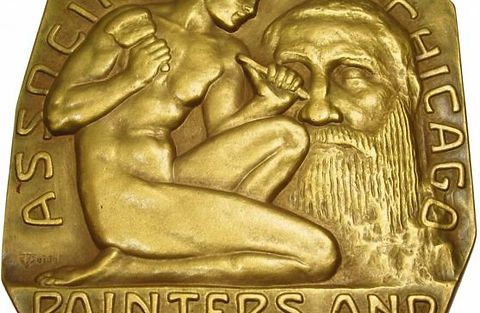

Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors Gold Medal

Click to view full image

Charles W. Dahlgreen - Jules Brower Prize - Art Institute of Chicago - 1934

Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors

Modern Art Arrives in Chicago

The story of the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors cannot be understood without first situating it within the larger cultural shockwave that modern art delivered to the United States in the early twentieth century. When modernism arrived in Chicago, it did so not with subtlety but with a force that disrupted long-standing artistic traditions and split the city’s art community into warring factions. This rupture ultimately led to the formation of the Association—an organization expressly committed to preserving conservative standards of artistic craftsmanship and aesthetic “sanity” in an era when many believed art was slipping into chaos.

Modern art’s dramatic entrance into Chicago was heralded by the 1913 Armory Show, whose touring exhibition challenged preconceived notions of what art should be. Newspaper coverage reflected a mixture of fascination, bewilderment, and moral panic. Harriet Monroe’s Chicago Tribune headline famously described the show as “BEDLAM IN ART,” invoking a term historically associated with an infamous London asylum for the mentally ill.[1] The metaphor was hardly accidental; to many observers, the works on display appeared not simply unconventional but pathological. Monroe doubled down the following day with another sensational headline, “Art Show Opens to Freaks,” editorializing that the exhibition “teems with the bizarre.”[2] Her rhetoric set the tone for how Chicagoans would receive this unprecedented visual vocabulary.

The public reaction intensified once the show opened at the Art Institute of Chicago on March 24, 1913. Visitors lined up in droves, curious to witness the spectacle they had been primed to expect. Newspapers recorded the shock and hostility expressed by viewers who regarded Cubism, Futurism, and other avant-garde styles as evidence of cultural degeneration. One period critique even suggested that extended contemplation of such works might induce madness. The Chicago Record-Herald described the artwork as “blasphemous innovation,” pairing aesthetic judgment with moral condemnation.[3] Effa Webster of the Chicago Examiner asserted that the Art Institute had been "desecrated," calling the exhibition an “insult to a self-respecting Chicago public.”[4] These reactions illustrate the extent to which modern art was viewed as an affront—not merely to taste, but to civic identity.

Even Art Institute Director William M. R. French added to the chorus of disapproval, warning that the “bad influence” of the exhibition would linger in Chicago and that its “unartistic manner” and “immoral subjects” would not serve the public interest.[5] With this institutional resistance firmly in place, Chicago established itself early as a battleground in the fight over modern art.

Conflicts and With Modern Art

Although the 1913 Armory Show opened eyes and closed minds, it was not until 1919 that modernism gained meaningful traction among younger Chicago artists. This shift occurred with the arrival of George Wesley Bellows, a prominent painter associated with the New York "Ashcan School," who joined the faculty of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Bellows, whose work had appeared in the Armory Show, was known for his experimental disposition and engagement with contemporary artistic developments.[6] His influence on Chicago’s students proved profound.

Guided by the teachings of Robert Henri, Bellows encouraged students to draw inspiration from the gritty realities of urban life rather than from academic conventions. Chicago, with its soot-laden air, overcrowded tenements, bustling industrial corridors, and ceaseless social dynamism, offered fertile ground for this approach. Bellows’ classes helped cultivate a cohort of young artists who embraced modernism not as a threat but as an opportunity for expressive renewal.[7] These artists would play pivotal roles in shaping the eventual conflict that led to the formation of the Association.

Tensions escalated in 1921 during the Annual Exhibition by American Artists at the Art Institute. Several younger, modern-leaning artists grew frustrated with the jury's conservative selections. When the artists requested a supplementary display area for works rejected from the official exhibition—and were denied—they organized their own counter-exhibition: Chicago’s first Salon des Refusés, held at the Rothschild department store.[8] Critics observed that the organizers harbored no personal animosity toward traditionalists but believed the public deserved exposure to the innovative work being marginalized by conservative jurors.[9]

The Salon’s bold advertising campaign—promising “the new, the different, the bizarre”—captured public attention and challenged the Art Institute’s cultural gatekeeping. Though sensational in tone, the exhibition marked a critical turning point: it signaled both the confidence of modernist artists and their growing willingness to openly contest institutional authority. Clarence J. Bulliet later emphasized the event’s significance, noting that the Salon’s popularity catalyzed the founding of the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists, a group committed to bypassing conservative juries entirely.[10]

To understand the stakes of these conflicts, one must appreciate the importance of the Art Institute’s Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity. Established in 1897 under the auspices of the Chicago Society of Artists, the Chicago and Vicinity rapidly became a prestigious venue through which artists could secure recognition, sales, and awards.[11] By 1922, the exhibition offered nineteen major prizes, attracted reviews from all major newspapers, and hosted dozens of community groups.[12] Acceptance into the Chicago and Vicinity could significantly advance an artist’s career; rejection could impede it. Consequently, control over the exhibition jury equated to tremendous influence over the direction of Chicago art.

By 1922–23, modernists had gained substantial influence within the Chicago Society of Artists, prompting growing alarm among conservative members. A proposed change to jury procedures ignited controversy. Sculptor Emil Zettler and painters Carl Hoeckner and Gordon Saint Clair circulated a petition warning that the alterations would restrict the diversity of works accepted into the Chicago and Vicinity.[13] Although only the provision for secret ballots was adopted, the debate exposed deep philosophical schisms.

It was against this backdrop that the conservative countermovement began to organize. In early 1923, approximately fifty artists founded a new group, initially called The Painters and Sculptors of Chicago, in direct response to what they saw as modernist domination of the Chicago and Vicinity jury.[14] Lorado Taft, one of Chicago’s most respected sculptors, served as the group’s first president. The organization adopted the motto mens sana — “a healthy mind”—implicitly contrasting their supposedly rational, disciplined approach to art with the perceived madness of modernism. Their stated objective was to uphold “standards of craftsmanship” and “high ideals,” a clear rebuke to the avant-garde tendencies reshaping the Chicago art world.[15]

The timing of the group’s organization was no coincidence. The 1923 Chicago and Vicinity had opened only days earlier, and conservative artists were already voicing their dissatisfaction.[16] Although the jury had been relatively balanced numerically, the three-person hanging committee consisted primarily of modernists.[17] Critics noticed the unconventional arrangement of the exhibition, and conservative Tribune critic Eleanor Jewett relayed a telling anecdote in which two businessmen mocked the “crazy pictures” and asserted that such works never sold. Jewett used the anecdote as a springboard for broader denunciations of modern art.[18]

In 1923, by a “coup,” certain radicals got onto the jury. Five “abstracts” by Flora Schofield came up for consideration, and three of them were voted into the show. An acrid debate ensured between Pauline Palmer, Mrs. Schofield’s personal friend but art foe, and Carl Hoeckner, champion of the “radicals.”

Formation of the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors

The fury of this debate was carried into the next business meeting of the Chicago Society of Artists, with the result that Mrs. Palmer and her friends withdrew and formed the new Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors.[19]

This act of secession demonstrated the depth of frustration felt by traditionalists. One conservative artist lamented retrospectively that they had “gone asleep at the switch” and allowed modernists to take over their organization.[20] Their new group, initially envisioned as a sub-organization within the Chicago Society of Artists, rapidly grew more autonomous as ideological divisions hardened.[21]

Early Exhibitions and Institutional Rivalry

By 1925, the Painters and Sculptors of Chicago held their first independent exhibition, featuring approximately forty artists, at Carson Pirie Scott’s department store galleries.[22] This event marked the beginning of a long campaign to establish a conservative alternative to modernist-dominated venues. Though the group participated in the Chicago and Vicinity during some subsequent years, the rift grew ever wider. In 1926, the Chicago Society of Artists declined to award its prestigious Silver Medal at the Chicago and Vicinity; by 1927, the Chicago Society of Artists held a separate exhibition altogether, awarding its top prize to the modernist painter Increase Robinson.[23]

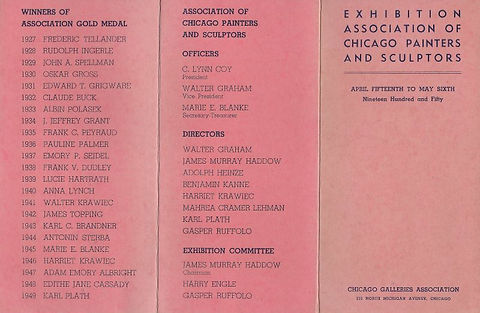

The conservative faction, refusing to be overshadowed, instituted its own highest honor—the Gold Medal—awarded for the first time in 1927 to Frederic Tellander for his painting Surf at Ogunquit.[24] The stage was set for nearly a decade of escalating rivalry, parallel exhibitions, and deepening philosophical division. In October, fifty-one member artists exhibited eighty-two works at the rooms of the recently formed Chicago Galleries Association, 220 N. Michigan Ave.[25] Artists were limited to two entries each.[26]

Awards and Growth in the Late 1920s

By the late 1920s, the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors had become an established force within the city’s artistic landscape. In 1928, their Gold Medal, awarded annually at the Chicago and Vicinity for the “most meritorious work” by one of their members, went to landscape painter Rudolph Ingerle.[27] The award affirmed the group’s identity as the guardian of traditional craftsmanship at a moment when modernism was ascendant. In 1929 the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors held its own exhibition that was widely praised by conservative critics. Eleanor Jewett described the show: “The effect is one of brilliancy.…Each individual contribution is good and some of the canvases have more than usual merit.”[28] Nine days later she added, “The paintings are so excellent and so characteristic of the different artists that it is almost impossible to submit anything in regard to them but appreciation.”[29]

Other reviewers echoed this praise. One critic noted that although no sculpture appeared in the 1928 exhibit, the paintings were colorful, carefully composed, and representative of a wide range of subjects. He contrasted these works with what he derisively termed “anecdotal” modernist painting—implying that modernist narratives were contrived or overly intellectual, whereas the Association upheld sincerity and artistic integrity through representational clarity.[30]

By 1928, Pauline Palmer—one of the central figures in the 1923 split—had been nominated as President of the organization, further cementing the group’s leadership around established, decorated artists.[31] Award recognition continued into the next decade: Oskar Gross won the Association Gold Medal in 1930, followed by Edward Thomas Grigware in 1931 at the Chicago and Vicinity show.[32] These awards underscored the group’s belief in disciplined draftsmanship and compositional harmony as the foundation of serious artmaking.

The Academy vs. Modernism in the 1930s

Yet just as the Chicago Academy of Painters and Sculptors appeared secure in its identity, the relationship between conservative and modernist factions within Chicago reached a new breaking point. The year 1932 proved especially pivotal. Although the Chicago and Vicinity remained the central annual exhibition in Chicago’s art calendar, Association members staged an unexpected and dramatic boycott that year. When the Chicago and Vicinity opened on January 28, 1932, many of the city’s most prominent conservative artists were conspicuously absent from the exhibition. Instead, on January 31 — only three days later — the Association opened a separate exhibition at the Shawnee Country Club in suburban Wilmette.[33]

The decision to hold a simultaneous competing exhibition represented a bold public protest. Of the forty artists who exhibited in Wilmette, only eight also appeared in the 1932 Chicago and Vicinity, even though most had long-standing histories of participation. The withdrawal was nearly total and unmistakably intentional. Even Albin Polasek, Head of Sculpture at the Art Institute, abstained from submitting work, underscoring the seriousness of the conservative revolt.[34]

Eleanor Jewett's review of the Wilmette exhibition captured the Association’s ideological posture. Her headline declared: “Sane Paintings at Club Show Win Approval: Refuse to Retreat Before Modernism.”[35] The language is revealing—not only was modern art deemed incorrect or disagreeable; it was portrayed as a force from which one must refuse to “retreat,” as though engaged in a cultural battle. Jewett’s commentary further emphasized that the exhibition offered a refreshing alternative to the bold experimentation dominating the Art Institute’s recent shows. She celebrated the Wilmette display as a sanctuary of clarity and sound technique, free from the perceived excesses of the avant-garde.

C. J. Bulliet, writing for the Chicago Evening Post, observed a similar dynamic at the central Chicago and Vicinity exhibition. He noted that the “old-hats”—his term for conservative painters—were nearly as absent in 1932 as they had been in the preceding season’s American exhibition. Modernists, meanwhile, were “offended” for a different reason: the first prize had been awarded to a conservative work, Girl Reading, which stood out amid an otherwise modern-leaning collection. Bulliet pointedly remarked that after the trustees finished their initial jurying, “Buck’s painting was about the only tiresome academic thing left”.[36] Yet curiously, Girl Reading won not only the Chicago and Vicinity first prize but also the Association Gold Medal that year — a rare coincidence that momentarily united opposing factions, even as tensions continued to rise.[37]

Following the Wilmette exhibition, the Association returned to the city in June 1932 with a show at the Chicago Galleries Association. Jewett again praised the display’s “colorful” and “interesting” qualities, positioning it as a welcome reprieve from the recent Art Institute exhibitions.[38] Another critic concurred, suggesting that those disappointed by the Chicago and Vicinity’s modernist emphasis would “find solace” in the Association exhibit.[39] The conservative artists had, for the moment, reclaimed their audience.

In 1933, however, the Art Institute attempted to address ongoing complaints about jury selection. The catalog for the thirty-seventh Chicago and Vicinity listed two separate painting juries—one modernist, one conservative—to placate both sides.[40] The modernist jury consisted of younger artists such as Francis Chapin, Louis Ritman, and Flora Schofield, while the conservative jury featured Edgar Spier Cameron, Rudolph Ingerle, and Pauline Palmer. Jewett found the resulting exhibition confusing: modern and conservative works were intermingled in a way that created what she called a “curious show,” with extremes of style placed side by side.[41]

The awarding of prizes further inflamed tensions. Critic Jewett called the annual exhibit “a curious show….There is a mingling of modern and conservative work sufficient to make one’s head whirl. The two kinds of painting are so diametrically opposed that one wonders who can find satisfaction in both.” She noted that except for two, all the prizes awarded went to Modernists. In voting the prizes the three Modernists deadlocked with the three Conservatives and the three sculpture jurists were called in to break the tie. Two of those three being Modernists, the awards were swayed in that direction.[42]

Bulliet offered a more satirical critique. He reminded readers that conservative artists had previously threatened to join the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists, abandoning the Chicago and Vicinity entirely unless their demands were addressed.[43] The Art Institute, in response, had conceded to dual juries; yet both factions ultimately found the resulting exhibition dull and uninspired. Bulliet attributed this to the role of the jurors themselves, whom he blamed for making “allegedly stupid choices.”[44] His commentary reflected broader fatigue with the longstanding feud, suggesting that the compromise had satisfied no one.

A brief respite from these disputes came with the opening of the Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933. The Association presented work in the Fair’s Home Planning Building, and even Jewett lamented that some of their paintings were not also included in the official Art Institute exhibition celebrating American art.[45] But the peace proved fleeting. As the 1934 Chicago and Vicinity approached, conservative organizations—including the Association, the Palette and Chisel Club, and the Oak Park Art League—submitted a formal protest to the Art Institute’s trustees. Their letter demanded that future exhibitions be judged exclusively by artists rather than by laypeople or external professionals.[46]

Bulliet described the artists as “deeply and ominously aroused,” noting that he had never seen such intense indignation among Chicago painters.[47] Jewett pointed out that, in their letter, the artists had curiously omitted concerns about the prize jury, which was often separate from the selection jury.[48] Nevertheless, the protest signaled that conservative artists were no longer content merely to complain about jury bias; they were now prepared to withdraw from the Chicago and Vicinity entirely unless substantial reforms were made.

The 1934 Chicago and Vicinity did little to soothe frustrations. The selection jury consisted largely of curators from institutions outside Chicago—Detroit, Baltimore, Buffalo, and Indianapolis—along with a Chicago architect.[49] The resulting exhibition strongly favored modernists, both in number and visibility. Although one conservative work, J. Jeffrey Grant’s Street Scene in Gloucester, won the Association Gold Medal that year,[50] the broader display reaffirmed the Art Institute’s increasing alignment with modernism.

Incorporation and Mid-Century Challenges

Faced with these cumulative frustrations, the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors took a decisive organizational step. On November 15, 1934, the Association formally incorporated in the State of Illinois, solidifying its legal and institutional identity.[51] Its constitution declared its purpose “to promote social friendship, to encourage the best standards of craftsmanship, to cultivate the pursuit of high ideals and to develop American art. Mens Sansa.”[52] The wording reasserted the group's foundational belief: that art should aspire toward moral and technical clarity, resisting the perceived distortions of modernism.

Eighty-two artists were listed as founding members. Their ranks included many of Chicago’s most accomplished and respected practitioners: Adam Emory Albright, Ralph Elmer Clarkson, Frank Virgil Dudley, Ernest Martin Hennings, Pauline Palmer, Frank Charles Peyraud, Albin Polasek, Anna Lee Stacey, and Lorado Taft. These were artists with extensive prize histories, solo exhibitions at the Art Institute, and deep ties to the School of the Art Institute. Their presence lent the Association a sense of authority and continuity with Chicago’s artistic past—precisely the legacy they sought to preserve.

Despite its impressive roster and strengthened organizational identity, the newly incorporated Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors faced a rapidly shifting cultural landscape. Modernism continued to gain institutional legitimacy. Younger artists embraced abstraction and experimentation; museums increasingly championed avant-garde movements; and the broader national art market—especially in New York—shifted decisively toward innovation rather than tradition. Although the Association remained an influential force among Chicago’s established artists, its exhibitions and aesthetic principles were gradually overshadowed by the accelerating pace of change in American art.

Nevertheless, during the early years following incorporation, the Association maintained a robust presence within Chicago’s exhibition circuit. Members continued to participate selectively in the Art Institute’s Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity, though always under protest regarding jury procedures. Their independent exhibitions also continued, often receiving favorable coverage from critics who shared their skepticism toward modernism. Eleanor Jewett, long one of the most visible voices defending traditional craftsmanship, consistently framed Association exhibitions as bastions of order amid what she perceived as the disorderly excesses of contemporary experimentalism.

The Association’s identity rested on several pillars: mastery of technique, adherence to representational clarity, respect for historical artistic traditions, and resistance to what members saw as the intellectual pretensions and visual distortions of the modernist aesthetic. Their exhibitions rarely included abstraction, surrealism, or other experimental forms. Instead, they favored landscapes, portraits, still life, and genre scenes—subjects that had long anchored American art and that aligned with the group’s commitment to what they described as “high ideals.”

But in the broader artistic climate of the 1930s, these commitments increasingly positioned the Association as countercultural rather than conventional. The Great Depression and the rise of federal art programs—most notably the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA)—gave unprecedented visibility to socially engaged art, including the murals and regionalist paintings that became hallmarks of the era. Though many Association artists participated in federal art programs, the organization itself remained focused on aesthetic rather than political aims.

The tensions between modernist and conservative approaches were reflected in critics’ commentary during this period. For example, when examining the 1934 PWAP debate, Jewett noted that the newspaper’s headline—“Public Works of Art Project in Chicago Moves Workers with Palette and Chisel to Hot Debate”—was misleading, for the content of the article bore little relation to the title.[53] Her observation underscores the ongoing cultural confusion surrounding art movements and artistic intent; newspapers often sensationalized perceived conflicts within the art community, particularly when modernism was involved.

By the late 1930s, dual juries at the Chicago and Vicinity exhibitions had become more common, with the Art Institute attempting—though never fully succeeding—to create an atmosphere of balance between modern and conservative sensibilities. Yet the Chicago and Vicinity catalogues and critical reviews from this period demonstrate that modernism continued its steady advance. The traditional safeguards that conservative artists fought to implement could not stem the tide of aesthetic change.

The Chicago Galleries Association, an organization formed in 1925 to support the sale and exhibition of works by Midwestern artists, continued to support the Association. These exhibitions helped Association members sustain its public visibility and generate sales, which were especially critical during the economic hardships of the 1930s. Critics frequently praised the exhibitions' “soundness” and “color,” reinforcing the idea that the Association offered an accessible alternative to more challenging modernist displays.

As the 1940s progressed, however, the both Association’s influence waned. Broader shifts in the American art world increasingly favored New York as the center of artistic activity, notably with the rise of Abstract Expressionism. Chicago, though still home to important artists and institutions, no longer held the cultural dominance it once enjoyed. The Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, oriented toward more traditional aesthetics, found itself increasingly at odds with the dominant currents reshaping American art.

Still, the group persisted. Annual exhibitions continued, membership remained active, and Association artists continued to garner awards at local and regional shows. Their dedication to representational art ensured that they retained a loyal audience, even as artistic tastes changed. And while the Association’s stance against modernism placed it outside the avant-garde, it provided a space where conservative artists could thrive, collaborate, and receive recognition.

Decline and Legacy

By the mid-1950s, however, the organization’s activity began to show signs of decline. Newspaper archives suggest that the Association’s last annual exhibition took place in 1956, held at the Palette and Chisel Club—another long-standing Chicago institution supportive of representational art. The choice of venue was symbolic. The Chicago Galleries Association, which had hosted numerous Association exhibitions over the years, closed in 1956, eliminating a major platform for the group’s public visibility. Without access to a central gallery space, and with modernism firmly entrenched in both academic and museum settings, the Association struggled to maintain its earlier prominence.

Jewett's review of the 1956 exhibition offers a glimpse into the organization’s final public chapter. She described the show as exhibiting “sound art,” praising the quality of the works while also acknowledging the shifting cultural landscape in which the Association now operated.[54] Her review implicitly recognized that while Association artists continued to produce high-caliber representational art, the broader public conversation had moved on. The group’s ideals, once foundational to Chicago’s art identity, now belonged to a past era.

The dissolution of the Association is not formally documented, but its absence from records after 1956 indicates that the organization quietly receded as its members aged and as cultural priorities evolved. Yet the Association’s legacy is significant. The group preserved and championed an artistic tradition that might otherwise have been overshadowed in Chicago’s modernist narrative. Its exhibitions provide invaluable insight into the city's diverse artistic output, demonstrating that Chicago’s art history cannot be understood solely through the lens of modernist innovation.

Lessons From the Advent of New Art Movements

Moreover, the history of the Association underscores the dynamic tension between tradition and change in American art. At moments of artistic transformation, debates over aesthetics become debates over identity, values, and cultural purpose. The Association was born from such a debate—a response to a perceived erosion of standards, a desire to uphold a vision of art rooted in clarity, craftsmanship, and continuity with the past. Whether one embraces or critiques their perspective, the Association reveals how deeply artists can feel invested in the cultural meaning of their work.

The organization also represents a pattern that recurs throughout art history: when disruptive new styles emerge, established practitioners often respond by forming groups that seek to preserve earlier traditions. Such groups can be dismissed as reactionary, but they also play a vital role in the cultural ecosystem by articulating alternative values and preserving diverse artistic practices. The Association served precisely this function in Chicago for more than three decades.

As modernism reshaped the art world, the Association offered a counterbalance, reminding audiences that innovation does not need entirely eclipse tradition. Their persistence, even in the face of diminishing institutional support, reflects a deep commitment to principles they believed essential for the health of American art. Their influence may have waned, but their presence shaped the artistic dialogue of their time.

The decline of the Association also coincided with changes in how American audiences engaged with the visual arts. By the mid-twentieth century, museums, critics, and collectors increasingly favored experimental approaches. Academic institutions adopted modernist curricula. Younger artists gravitated toward abstraction, conceptualism, and other non-representational forms. In this environment, groups like the Association struggled to maintain relevance—not because their art lacked quality, but because cultural narratives shifted around them.

Moreover, the rise of New York as the epicenter of American art further diminished the influence of regional organizations like the Association. Chicago, though still a vibrant artistic center, no longer set national trends. Critics, galleries, and collectors increasingly looked to New York for leadership, and movements such as Abstract Expressionism captured the public imagination on a scale that overshadowed the representational traditions the Association sought to protect.

Yet the importance of the Association as a historical counterpoint should not be underestimated. Their exhibitions, awards, and public presence contributed to a pluralistic artistic landscape in Chicago. They challenged modernist dominance, articulated alternative aesthetic ideals, and created a community for artists committed to representational and traditional forms.

By tracing the evolution of the Association—its origins in protest, its battles over jury control, its institutional consolidation, and its eventual decline—we gain a fuller understanding of the complex interplay between artistic movements in Chicago. The group’s history offers valuable insight into the cultural tensions that accompany artistic innovation and reminds us that the development of American art has never followed a single, linear trajectory.

Today, the history of the Association invites reconsideration not just of the group itself, but of how we understand artistic value and progress. It challenges the common narrative that positions modernism as a triumphant force and traditionalism as a mere obstacle. Instead, the Association reveals that traditional art forms can serve as meaningful, substantive responses to cultural change—responses that deserve recognition for their artistry, conviction, and contribution to the cultural fabric of their era.

In the end, the Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors leave behind a legacy defined not by the duration of its existence but by the depth of its conviction. Formed in a moment of ideological fracture, sustained through decades of aesthetic debate, and dissolved quietly as the world changed around it, the Association serves as a testament to the enduring significance of artistic communities built on shared values and mutual support. Its story enriches our understanding of Chicago’s artistic identity and offers a compelling example of how artists navigate—and shape—the shifting landscape of cultural history.

[1] The original meaning of the word “bedlam” came from a reference to an asylum for the mentally ill. Bedlam was the colloquial name, derived from Bethlem, for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem in London, England.

[2] Harriet Monroe, “Art Show Open To Freaks,” Chicago Tribune, February 17, 1913.

[3] “Recent Example of Cubists’ Art,” Chicago Record-Herald, March 19, 1913 (AIC Scrapbooks) vol. 30, 58.

[4] H. Effa Webster, “Moderns Here On Exhibition Called Art Desecration,” Chicago Examiner, April 1, 1913.

[5] “Director French Fears Cubists’ Chicago Effect,” Chicago Examiner, April 27, 1913.

[6] https://www.nadatabase.org/2018/07/17/george-wesley-bellows/ accessed January 8, 2022.

[7] The Illinois Historical Art Project has compiled an extensive database of artists and the professors they studied with at the School of the Art Institute.

[8] Salon des Refusés of 1921, (Chicago: Rothshild & Company, November 21, 1921) [exhibition catlaog]. “Chicago’s First Salon Des Refusés...,” The Arts, Vol. 2, November 1921, pp.97-98. “Irate Artists Ask Rejected Art Showing,” Chicago American, November 4, 1921 in Art Institute of Chicago scrapbooks, vol. 42, p.118, [pages out of sequence]. “Art ‘Insurgents’ To Hold Exhibit,” Chicago Herald Examiner, November 14, 1921, vol. 42, approximately p.118. [out of sequence] “Chicago Artists Ask Their Work Be Displayed,” Chicago Evening Post, 11/4/1921, vol. 42, approximately p.118 [out of sequence].

[9] Lena M. McCauley, “Salon des Refuses to appear Here” in “News of the Art World,” Chicago Evening Post, November 15, 1921, p.11.

[10] Clarence J. Bulliet, “Artists of Chicago Past and Present,” Chicago Daily News, No. 11 in a series, Rudolph Weisenborn, May 4, 1935, p.11.

[11] The Catalogue of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Exhibition By Artists of Chicago and Vicinity, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, January 26-March 5, 1922).

[12] “Chicago Painter Made Target Of Artists’ Attacks,” Chicago Evening Post, 5/22/1922 and Marguerite B. Williams, “Art Institute Rules Roil Chicago Society,” Chicago Daily News, 5/24/1922 and “Artists Vote Down ‘Outside Jury’ Rule,” Chicago Journal, 5/26/1922, all in Art Institute of Chicago Scrapbooks, vol. 43.

[13] “Art on Trial,” illustration, Chicago Herald-Examiner, 1/23/1923 in Art Institute of Chicago Scrapbooks, vol. 44.

[14] “A New Society In Chicago,” American Magazine of Art, Vol. 14, July 1923, p.341. Eleanor Jewett, “Art And Artists,” Chicago Tribune, 4/15/1923, part 7, p.14. John Franklin Stacey (1859-1941) served as Vice-President and Carl Rudolph Krafft (1884-1938) as Secretary-Treasurer. Directors included Karl Albert Buehr (1866-1952), Lucie Hartrath (1867-1962), Charles William Dahlgreen (1865-1955), Pauline Palmer (1867-1938), Frederick Cleveland Hibbard (1881-1950), and Frank Virgil Dudley (1868-1957).

[15] Op. cit., American Magazine of Art, 1923, p.341.

[16] Thomas Temple Hoyne, “Show Visitor Shocked By Paintings,” Chicago American, February 6, 1923 in Art Institute of Chicago scrapbooks, vol. 44.

[17] “Painters Rush To Defense Of ‘Modernistic’ Art,” Chicago American, February 7, 1923 in Art Institute of Chicago scrapbooks, vol. 44. The author has used his knowledge of the juror’s backgrounds to estimate those in each camp. The Annual Exhibition Record of the Art Institute of Chicago 1888-1950, (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1990), p.30.

[18] Eleanor Jewett, “Art and Artists,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1923, part 7, p.9. Eleanor Jewett, “Art and Artists,” Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1923, part 7, p.9.

[19] Clarence J. Bulliet, “Artists of Chicago Past and Present,” “No. 89 - Flora Schofield,” Chicago Daily News, June 3, 1939, Art and Antiques Section, p.1.

[20] Op. cit., Chicago Journal, March 31, 1923.

[21] “‘Painters and Sculptors’ Will Attend Parent Group’s Meeting,” Chicago Journal, March 31, 1923, in Art Institute of Chicago scrapbooks, vol. 45.

[22] Sixty artists formed the original group. Lena M. McCauley, “Painters, Sculptors Open Annual Show,” Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, March 31, 1925, p.3.

[23] Inez Cunningham, “Art by Chicagoans on Display Today; Prizes Are Awarded,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1926, p.25. Charles Victor Knox, “Chicago Society of Artists Exhibiting,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, November 8, 1927, p.6. The prize was awarded her Market, illustrated in the November 22, 1927 issue, p.4.

[24] “Artists Award New Chicago Show Prize,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, February 1, 1927, p.12. “Painters and Sculptors Medal Given Tellander,” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1927, p.27.

[25] The Chicago Galleries Association was formed at the end of 1925. The best description of the organization was reprinted in 1926: “The Chicago Galleries Association is a not-for-profit corporation organized by the Municipal Art League of Chicago, to sell the works of Art of the Best Artists of the Middle West and western States.” “A Circulating Art Gallery,” All Arts Magazine, Vol. II, No. 8, August 1926, p.18.

[26] The Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors Invite You To The Opening Of Their Annual Exhibition, (Chicago: Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, October 20, 1927).

[27] Eleanor Jewett, “News of Art and Artists,” Chicago Tribune, 3/25/1928, part 8, p.4. “Art Notes,” Chicago Tribune, April 1, 1928, part 8, p.8.

[28] Eleanor Jewett, “Chicago Painters and Sculptors Exhibiting at Local Galleries,” Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1929, p.35.

[29] Eleanor Jewett, “Paintings and Sculpture Win High Praise,” Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1929, part 7, p.3.

[30] Charles Victor Knox, “Association Of Chicago Painters And Sculptors Holds Exhibition,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, June 25, 1929, p.7.

[31] American Art Annual, Vol. XXV, 1928, p.96.

[32] Eleanor Jewett, “Chicago Art How Opens; Prizes Given,” Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1931, p.20. Exhibition. Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, (Chicago: Assoc. of Chicago. Painters and Sculptors, 1950), lists the Gold Medal winners from 1927 onward.

[33] “Show at Shawnee Club,” Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1932, p.14.

[34] Eleanor Jewett, “Sane Paintings at Club Show Win Approval: Refuse to Retreat Before Modernism,” Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1932, p.13.

[35] Eleanor Jewett, “Sane Paintings at Club Show Win Approval: Refuse to Retreat Before Modernism,” Chicago Tribune, February 13, 1932, p.13.

[36] C. J. Bulliet, “Chicago and Vicinity Show at the Institute Again Rings the Matin Bell,” Chicago Evening Post, February 2, 1932, Art Section, p.1. The painting is illustrated in Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, Vol. 26, No. 3 (March 1932), p.39. “Honors Awarded By The Art Institute of Chicago,” Thirty-Sixth C, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, January 28-March 20, 1932), n.p.

[37] “Honors Awarded By The Art Institute of Chicago,” Thirty-Sixth Annual Exhibition By Artists Of Chicago And Vicinity, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, January 12-March 5, 1933), n.p. The award was given after the printing of the C&V catalog, hence the following year the prize is listed.

[38] Eleanor Jewett, “Good Painting Marks Display of Art Group: Painters and Sculptors Hold Exhibition,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1932, p.19.

[39] Tom Vickerman, “You Didn’t Like the Last Chicago Show? Well, Try This One,” Chicago Evening Post, June 7, 1932, Art Section, p.2.

[40] “Juries Of Selection,” Thirty-Sixth Annual Exhibition By Artists Of Chicago And Vicinity, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, January 12-March 5, 1933), n.p.

[41] Eleanor Jewett, “Moderns Win Dispute Over Art Awards,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1933, p.15. Eleanor Jewett, “First Glimpse of Annual Show by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity,” Chicago Tribune, January 15, 1933, part 8, p.3.

[42] Eleanor Jewett, “Moderns Win Dispute Over Art Awards,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1933, p.15. Eleanor Jewett, “First Glimpse of Annual Show by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity,” Chicago Tribune, January 15, 1933, part 8, p.3.

[43] C. J. Bulliet, “Bulliet’s Artless Comment,” Chicago Daily News, January 21, 1933, p.7.

[44] Op. cit., Chicago Daily News, January 21, 1933, p.7.

[45] Eleanor Jewett, “City’s Famous Artists Show Work At Fair: Hang Paintings in Home Planning Building,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1933, p.19.

[46] Eleanor Jewett, “Public Works of Art Project in Chicago Moves Workers with Palette and Chisel to Hot Debate,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1934, part 7, p.6. Note that the article title was a newspaper error as the content did not relate to the title.

[47] C. J. Bulliet, “Bulliet’s Artless Comment,” Chicago Daily News, March 3, 1934, p.24.

[48] Op. cit., Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1933, p.19.

[49] “Jury of Selection,” Thirty-eighth Annual Exhibition By Artists Of Chicago And Vicinity, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, February 1-March 18, 1934), n.p.

[50] “J. Jeffrey Grant Awarded Gold Medal for Painting,” Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1934, p.15. It was illustrated in the March 11, 1934, Sunday edition, part 7, p.6.

[51] “Constitution,” Association of Chicago Painters & Sculptors. Articles of Association, (Chicago: Association of Chicago Painters and Sculptors, 1934), p.3.

[52] Ibid. Articles III, IV, V, pp.4-6.

[53] Op. cit., Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1934, part 7, p.6.

[54] Eleanor Jewett, “Chicagoan’s Exhibit Has Its Sound Art,” Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1956, part 4, p.13.

[55] Op. cit., Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1956, part 4, p.13.

[56] Op. cit., Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1956, part 4, p.13.