Cubism in Chicago, the 1913 Armory Show

By Joel S. Dryer

Click to view full image

Armory Show 32-cent U.S. postage stamp showing Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase — iconic Cubist work.

Click to view full image

Post-Impressionism and Cubism at the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art — nudes and interior by Henri Matisse, illustrating early modernist works shown alongside Cubist art.

Impact of the International Exhibition of Modern Art - the Armory Show - on Chicago in 1913

In 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art — better known as the Armory Show — brought Cubism and modernism to Chicago, sparking controversy, confusion, and long-lasting influence on the city’s artistic development. This page traces the dramatic reactions, local reception, and eventual legacy of the movement in Chicago.

The Armory Show and the Arrival of Cubism in Chicago

Cubism in Chicago had a significant impact on art in the city. The International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show for its location at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York, opened there in February 1913. The show then traveled to Chicago and opened on March 24th. Its role in shaping modern art in Chicago, and its impact on the public, critics, artists, and patrons was long lasting. The show influenced our artists some years later, but it was in fact the Armory Show that brought modernism to Chicago. Most derided of all the works exhibited, were those of the Cubists. The movement had begun in Paris, then the epicenter of Western art. Post-Impressionism and Cubism were often intertwined and similarly scolded.

Origins of Cubism and Early Critical Reactions in Paris

But it was Matisse, of all people, who disparaged the Cubist’s art as nothing more than paintings made of small cubes. When influential dealer Daniel Kahnweiler opened a show of works by Georges Braque in the fall of 1908, critic Louis Vauxcelle wrote a review and used the term Cubism to describe what he saw. This new term from an influential critic lent weight to the movement. He had earlier coined the phrase Fauves or Wild Beasts in 1905 to describe works by Matisse and his like-minded contemporaries.

Matisse was probably not the one who should have been the one slinging mud. While revolutionary in the 1900s, even with today’s audiences his works take a bit of adjustment. The new schools, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, were somewhat confusing and confused at the time, all recognized as Post-Impressionism. But many recognized the influence of Manet in all of the movements.

Confusion, Criticism, and the Paris Salon of 1911

When the Paris Salon opened in 1911, the Cubists drew the most numerous and harshest comments. The earliest mention of Cubism in the New York Times was a review of this exhibition. The article aptly pointed out that the extraordinary productions were attracting all of the attention, and had become the main feature of the show. Unfortunately, even the critic for arguably the most comprehensive art section in the country was confused between what was Cubism and what was Fauvism and that in fact they were two separate and distinct movements.

Early Chicago Responses to Post-Impressionism and Cubism

Chicago critic Effa Webster was neither kind nor accepting. In her review she labeled the exhibit “Diabolical” and had quite a bit of vitriol to throw at the canvases calling them atrocious, mad, immoral, awful and degenerate. To be sure, this was a sign of responses to come.

Chicago Artists Engage with Modernism Before the Armory Show

One local artist, Jerome Blum, returned from Paris in 1911 and opened a show at W. Scott Thurber’s gallery in the Fine Arts Building. Chicago Daily-Inter Ocean newspaper critic and artist James William Pattison was open minded about Blum’s new style of painting, influenced as it was by his time in Paris. Pattison was to write extensively on Post-Impressionism in the July edition of The Fine Arts Journal, where he served as editor. His article featured four of Blum’s works.

Pattison arranged to give Blum space in his column to explain the new movements emanating from overseas. Blum reasoned that the work was no different from Rembrandt’s revolutionary use of light, or Whistler’s break-through use of tones to define space, or the Impressionists method of color and form. The new movements were just the same; revolutionary in theme and understandably hard to grasp. The Chicago Tribune’s Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry Magazine, was reasonably kind to Blum’s Post-Impressionism, asking the readers to give him a chance.

However, the rest of the Chicago press was having none of it; deriding the new movements with jibes such as this in the Chicago Examiner: “Mismated stockings, shoes, gloves and earrings, the odd eye and triangular smile now make fashionable women look like masterpieces by Futurists.”

Organizing the Armory Show and Bringing It to Chicago

The American Association of Painters and Sculptors in New York, led by their president Arthur Bowen Davies and secretary Walt Kuhn, had began organizing the Armory show by spending the fall of 1912 in Europe gathering works by artists whom others considered to be the most avant of the avant-garde. Their new association’s mission was to break free of the heretofore-strict juries that had little appreciation for the modern in art.

Three years earlier the Art Institute of Chicago had purchased Davies’ Maya, Mirror of Illusions. This work is a mystical representation of several female nude figures that were classically rendered using modern thinking, yet certainly not considered to be degenerate.

Organizer Walt Kuhn himself wasn’t clear on the meaning of all this modern art. He readily admitted to his wife that while the Cubists were, “intensely interesting, I sum them up as mostly literary… and lacking… in that passion or sex… which is absolutely necessary...” He even went so far as to call them “freaks.”

Public Outrage and Media Sensation in New York and Chicago

When the New York show opened in February 1913 it created an outright sensation where some 87,000 people turned out to see what many judged to be simply pranks. Throughout the run in New York, Davies and Kuhn were negotiating with the Art Institute to bring the show to Chicago. And when successful, Davies lauded the signing of a contract with the museum.

Harriet Monroe convinced Tribune editors to pay for a trip to New York and see the Armory Show. It was clear she had lost a short-lived patience with the new art movements when her headline on February 16th, 1913 ran “BEDLAM IN ART.” Little did the Chicago populace comprehend what was about to shake the foundations of everything they knew about art. It was Bedlam in Art, to be sure. This word, “bedlam,” has come into such popular use that the real impact of the word has been lost. It derives from Bedlam, in London. Bedlam was the popular name for the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem; an insane asylum. Miss Monroe was saying. INSANITY! MADHOUSE!

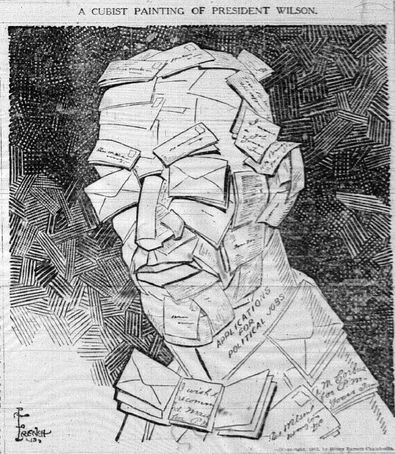

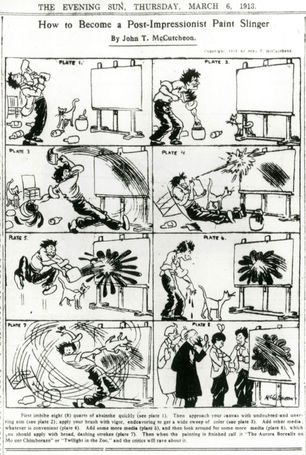

In a pamphlet Davies explained, “The time has arrived for giving the public an opportunity to see for themselves the results of new influences at work in other countries.” The king had already lost his clothing when Davies stated that it was “only for the intelligent to judge for themselves by themselves;” the implication of course was that if you did not see this art as symbolic of everything important, then you were obtuse. Kenyon Cox, who two years earlier had been a guest professor of life painting at the School of the Art Institute, was vociferous in his views against these new movements, and particularly against Cubism. Meanwhile the New York Press was having a fun time with the exhibit. They derided it in the worst way possible: through caricatures and comics, the most biting and graphic methods of the day. This modern sculptor was so enthralled with his work that it came to life, and then they fell in love.

Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, and the Chicago Firestorm

The painting that caused the biggest stir was Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. It was by all accounts the most viewed work of the entire show; called by one critic an “explosion in a shingle factory.” Audiences in New York had actually been angry that in this painting they could find neither the nude nor the staircase! When the show finally opened in Chicago, the press accounts were scathing. Even the Illinois Governor’s office became involved in an investigation to determine the immorality and indecency of it all. The governor’s investigators reported on the immoral and suggestive works. This only served to stir up significantly more interest. The show was a veritable earthquake, an Art Institute blockbuster, with an astounding 188,000 people paying to attend the bedlam on Michigan Avenue.

Collectors, Satire, and Institutional Anxiety in Chicago

Chicago collector and lawyer Arthur Jerome Eddy was the chief champion of Modernism in Chicago. He had previously built a sizeable collection of works by Whistler. During the Armory Show in Chicago, Eddy purchased far more works than any collector. A decade after his death, part of the collection came to the Art Institute, where much of it is on view today. Chicago had been braced for the arrival of the show. While it was on view in New York, local Chicago newspapers had hammered the art with frequent outlandish headlines. Harriet Monroe had noted that in New York, the crowds were flocking first to the Cubists and Futurists “eager to know the worst.” There were three basic responses she observed: “laughter, dumbstruck, or deep despair.”

How Chicago press viewed the exhibition is represented here. The artist is upside down and blindfolded; the painting quite comical. The Tribune announced that apparently the master hangers at the museum were having a difficult time determining which side of the paintings were right side up, and noted this was causing considerable debate among the installation crew.

In the Chicago Tribune's well-known column 'A line-O-Type or Two' appeared this poem:

“I did a canvas in the post-impressionistic style. It looked like Scrambled Eggs on Toast; I, even, had to smile. I said, ‘I'll work this Cubist bluff,’ With all my might and main, For folks are falling for the stuff, No matter how inane.’ I called the canvas ‘Cow With Cud,’ And hung It on the line. Altho' to me 'twas vague as mud, 'Twas clear to Gertrude Stein."

Art Institute Director William Merchant Richardson French was no fool. He conveniently departed with his wife for California the day before the show opened. He left in charge, executive secretary Newton H. Carpenter who had been purposely stoking the press to generate enough interest in the show to keep the gates full of paying visitors.

Morality, Censorship, and the Politics of Modern Art

Just two weeks earlier the subject of immorality literally had gone on trial in Chicago. In such close timing to the Armory Show it couldn’t be helped that it washed over charges of immorality cast upon the Cubists. A reproduction of the painting by French artist Paul Chabas entitled September Morn, winner of a gold medal at the Paris Salon, was shown that month at a local art store. Mayor Carter Harrison ordered his city art censor to march over to the art store and remove the offending work. The official municipal code stated: “No person shall exhibit…or sell…any lewd picture or other thing whatever of an immoral or scandalous nature.”

In hindsight, the Amory Show and its star performer Cubism was a promotional coup. The organizers deftly filled the newspapers with remarkable items, which like today, took on a life of their own. While the organizers were busy trying to justify the works in the show as not all “freakish” in an attempt to attract the conservative audiences of Chicago, their efforts successfully generated an extreme amount of curiosity. Crowds thronged to the Art Institute. One headline stated: “Society Rushes in To See Cubists.” On how to appreciate the art one critic stated: “Eat three welsh rarebits, smoke two pipe-fulls of hop and sniff cocaine until every street car looks like a goldfish and the Masonic Temple resembles a tiny white house.” The same critic noted “The cure for Cubism was two grains of potassium cyanide.” However, the show was a hit, in a wholly unexpected way as crowds rushed to stand shoulder to shoulder and see what all the commotion was about; and of course dutifully paid their entrance fee.

One of the more interesting press comments was by Robert Friedel, who owned a Chicago gallery. He said in a letter to the editor of the Chicago Evening Post: “The artists of the past have worked out many a great problem, but there are still as many more that remain obscure, and if we are going to go on repeating what are now commonplaces only, art is dead, and our modern artists are little better than parrots.” Friedel was a regular supporter of Chicago painters who painted in the conservative American Impressionist mode.

Art Institute professor Charles Francis Browne offered up a lecture in Fullerton Hall on how brilliantly stupid was this Cubist art. He stated, “It’s trying to prove itself by its own itness.” He commented sadly, “For the first time in ten years the hall was full for one of my lectures.” Art Institute students led the largest protests. This is quite perplexing when it is generally the students who are behind the newest trends, not vehemently opposed to them. On grounds behind the museum they burned facsimiles they had painted. A Tribune headline blared “Cubist Art Baffles Crowd.” As a final act of outrage the students held a mock trial of Henry Hair Mattress in reference to Henri Matisse. After the trial they dragged a straw effigy across the Michigan Avenue entrance while stabbing it with knives. It was reported a large crowd witnessed the event, and the police were called in to break up the disturbance. This quote from Art Institute Director William French, who conveniently returned from his vacation as soon as the show had vacated gives an idea of why Cubism and Modernism among our local artists lay dormant for several years: "I am afraid the bad influence of this exhibition will be felt in Chicago. The unartistic manner in which the majority of the pictures were painted and the LEWD and in some cases IMMORAL subjects will not be for the best... I fear."

The exhibit was creating a huge stir. Every newspaper was alive with such headlines as “Record Throngs at Institute Gape.” Or “Throng to See Cubists.” Chicago landscape architect Jens Jensen claimed that inadequate housing with flat walls and flat ceilings was causing the outbreak of Cubist art.

The Armory Show’s Aftermath and the Decline of Cubism in Chicago

Despite the negative reactions, Cubism came into the common vernacular. There were articles after the show closed about Cubist fashions, Cubist balls, Cubist music, Cubist poetry, Cubist literature, and even Cubist meals. Cubism was on everyone’s tongue, especially the young fashionable set. Cubist fashions were all the rage. It wasn’t long after the show closed that interest in Modernism died down considerably in Chicago.

World War I had broken out, and the new methods never had a chance to take hold here, especially without a supporting group of patrons. The route to success for a Chicago artist was the tried and true. Local lawyer Arthur Jerome Eddy, who had earlier been a strong proponent of Whistler, continued to amass a sizeable collection of Modernist works. And while many are now at the Art Institute, many more priceless works escaped Chicago.

Teaching, New Artist Groups, and the Slow Rise of Chicago Modernism

In 1919 George Bellows was invited to lecture for two months at the Art Institute while his work was hanging in a one-man show. Painter Randall Davey followed him that same year. Both of the artist’s works were shown at the Armory Show. Their arrival in Chicago was the beginning of the encouragement of young artists here to seek something entirely new, and break loose from the American Impressionism that had so dominated the town for decades. Bellows had told his students, “You don’t know what you are able to do until you try it. Try everything that can be done. Be deliberate. Be spontaneous. Be thoughtful and painstaking. Be abandoned and impulsive, intellectual and inspired, calm and temperamental. Learn your own possibilities.” This was a radical departure from the tried and true. Bellows later said in an interview: “The curious thing about conventionality is that while everybody criticizes it… everybody also sticks to it like a nail to a magnet.”

Several of the students who were at the Art Institute at the same time and had studied with both Bellows and Davey went on to form the Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists in 1922. The society's mission was to break free from the hidebound juries of the Art Institute; exactly as the organizers of the Armory Show had sought to do with their American Association of Painters & Sculptors eight years earlier. These students included Jean Crawford Adams, Frances Strain, Emil Armin, Fred Biesel, and Emile Grumieaux, among others. Some seven years later this same group of students, now in their early thirties, formed the Ten Chicago Artists. They held regular exhibitions at Marshall Field’s gallery, which had heretofore been the home of fairly conservative art.

Around the same time several other avant-garde groups formed in Chicago including the Neoterics and Neo Arlimusc. All of these organizations were comprised of artists who were seeking their own form of expression, something that was so evident with the Armory Show. For Chicago, after World War I and the Roaring Twenties, it seemed the time had finally arrived for the acceptance of non-traditional art and Chicago’s own brand of modernism.

Unfortunately for the Modernists, American Impressionism still had a firm grip on Chicago. Most of the artists in the modern mode needed other jobs to keep bread on the table. Rudolph Weisenborn founded several art organizations that did their best to exhibit and foster sales among patrons. Yet, like so many, his teaching supplemented what otherwise would have been a meager existence.

As early as 1923 there had been strife between the modern and conservative contingent of artists and a struggle to control the juries for annual shows at the Art Institute. The earliest call for “sane” art may have been by Tribune critic Eleanor Jewett when she stated, “Much of the modernist painting is destined for the scrap heap…The single sane avenue left is to investigate ways by which both the conservative and the modernist painter may have a fair chance to get their works before the public.”

Resistance to Modernism and the Society for Sanity in Art

As anti-modernist sentiment went, the Society for Sanity in Art was founded rather late. Members were against both abstraction and social realism. The group was founded by Josephine Hancock Logan whose by then deceased husband had funded the Logan Prize at the Art Institute. She had a strong negative response to Doris Lee’s painting that had been given the Logan Prize entitled Thanksgiving Day. Logan’s first reason for bringing this organization into being was “to help rid our museums of modernistic, moronic grotesqueries that were masquerading as art.” Her second reason was to “endeavor to reestablish authentic art in its rightful position before the public.” Members in her society held a sincere indignation for the prevailing art trends, which they labeled, “indiscriminate use of color, disregard for subject matter, distortion of nature and human form, and lack of structure in composition." The first exhibition catalogue of the Society, featured on the cover Claude Buck’s painting entitled Girl Reading, which five years earlier had garnered multiple prizes at the annual exhibit of Chicago artists at the Art Institute.

Art critics from the Chicago Daily News and New York Times blasted Josephine Logan for what they viewed as almost Fascist attempts to control art and creativity. Here we see artist Macena Barton accompanied by famed Daily News critic Clarence J. Bulliet, as well as Barton’s portrait of Bulliet in the Club’s collection. Bulliet wrote a series of one hundred and six articles on Chicago artists with the moniker you see at the top of the screen.

Legacy of the Armory Show in Chicago Art History

However, by this time the Century of Progress had come and gone and Modernism was firmly established in Chicago. Twenty years earlier the Armory Show with its then outrageous Cubism and modernism led the way, although it took two New York visiting professors, Bellows and Davey, to firmly establish modernism among a younger group of Chicago artists, eager to explore new trends.

Chicago has benefitted significantly with a thriving art scene filled with imaginative and innovative work. For this the Armory Show organizers are to be thanked. They brought Cubism to Chicago and opened the door to art unfettered of pre-conceived notions. Although initially derided, the Armory Show and Cubism opened Chicago to modernist ideas and indirectly shaped the next generation of artists.